Javelina 100 (Nov 2019)

This report is unorthodox. For those that read my blog from the Vermont 100 last year, you’ll be familiar that my post-race recaps aren’t chronological recounts of race-day, but rather general reflections that funnel into my running and, ultimately, the unfolding miles.

Running 100 miles is an achievement I’m proud of, however running isn’t everything. While I do spend a lot of time wearing running shoes, it’s merely part of my daily input. The outputs—what we leave behind, our footprints—deliver enduring impact. Truthfully, humans do far more important things than move our legs on roads or over mountains. As my coach Scott tells me when I get frustrated or tired: “It’s just running.”

Running certainly delivers varying degrees of meaning for different people. It’s all a deep, personal journey to figure out why we run, and what purpose it serves in our lives, if any. The single commonality is that we all run to navigate our twisting trails.

For me, there are the obvious enjoyments that keep me running, like getting in a flow-state on the trail—planting and pushing—my eyes & mind five strides ahead of my feet. It’s a spark. There’s also the pure vitality; contrary to what some might think, the more I run, the more energy I have. I’m also able to listen with more patience, although I’m still working on that skill (just ask my girlfriend, Lucy). Reaching a deeper level of thought is also attainable while running. As my feet land on the ground, my mind lands on new conclusions and new questions. Recovery is a factor, too. I enjoy the reward of rest when it’s earned, but not claimed. And lastly, there’s my innate opposition to stagnation, so I force forward progress. It’s a relentless list, but all ties into the reasons I lace-up my shoes.

So, yes, there’s a lot that keeps me moving.

But, the most influential reason I run is because of commitment.

FIRST COMES COMMITMENT

Commitment is a partner of accountability. To break it down, there is “the commitment” and “the accountability zone”. The hammer drops in the accountability zone; this is the “powerful” part that makes the commitment hold weight. If you commit to achieve X, then you receive Y; if you fail, you get Z. Nobody wants Z.

This commitment/accountability pairing is quite common, perhaps more than you might think: Democratic constituents hold elected leaders accountable for commitments made during campaigns, and they have a vote to ensure politicians follow-through. CEOs hold companies accountable to reach targets and KPI’s, while controlling employment and driving strategy. VC’s hold start-ups accountable with investment and ownership, sports coaches hold athletes accountable to perform at their highest levels, or else they get benched. The list goes on. Teachers hold students accountable with testing and grades used for university acceptance, parents hold their children accountable (or try), and activists hold society accountable for a collective cause, using tools like free speech & protest.

The duality of commitment and accountability is a system of check-and-balance to ensure people do what they are responsible for, or at least attempt to do so. Typically, the outcome is less important than the effort. While nobody wants “Z” (the negative outcome)—often times, even if someone fails, respect is earned when there’s an effort made.

This is why “the commitment” itself matters more than the outcome, which is particularly important when discussing this subject through the lens of ultrarunning.

After all, depending on the nature of the commitment, sometimes the outcome is out of the hands of “the committer”. There will always be uncontrollable variables and externalities. At some point we all surrender to unintended consequences, economic downturns, political climates, environmental change and so-on. For ultrarunners—typically “type-A”, anal people who crave control—a 100-mile race is about surrendering and embracing whatever comes-up, whether it’s injury, dehydration, illness, weather, gastro-intestinal issues, or mental swings. For some, surrendering to these factors could prove to be more challenging than the actual act of running.

The difference with a 100 mile event and other races, is that you’re committing to something that’s truly unknown. The only “known” entities of a 100 mile run is the distance, the course, and an approximate temperature/heat-index. The miles themselves unveil the numerous hidden mysteries.

I think about commitment and surrendering a lot, whether it’s while I run, at work, or with my family. Without raw commitment, 100 miles is unachievable.

Yet, there are varying types of commitment, and there’s a specific type that’s needed to train. The notion of self-commitment is what running is all about. Self-commitment is seldom seen, compared to accountability that’s externally-enforced. Think of this as bottom-up, opposed to top-down. Running 100 miles is always self-chosen, never given or demanded. It’s committing to a more difficult trail.

You can still hold others accountable while also committing to your own goals. In fact, the best leaders commit and hold others accountable, which cause ripple-effects around them.

If you see raw commitment and enforced consequences—you’re operating around the right people. In these cases, you’re more likely to follow suit, turn inwards, and make a personal commitment.

Some might refer to this as “inspiration”, or inspirational leadership.

We can dig even deeper on this topic. Good leaders hold others accountable; great leaders hold themselves accountable, and inspire others around them to do the same.

Indeed, it’s a harder, but more effective balance of commitment/accountability. For most people, it’s generally not “fun” to be held accountable to someone else or something else, especially for a reason you’re not passionate about. Personally, I wouldn’t be either. At work, I try to embody this with my team.

The idea is simple. Set a high-level vision for what needs to happen, and let people navigate there on their own. It’s a twisting trail, remember?

I use the following approach:

In order to reach XYZ goals for XYZ reasons, here are the things that need to get done.

I will hold you accountable.

Aside from that, pick the other things to hold yourself accountable for, which helps the company achieve its goals, and also bring you closer to reaching your personal goals at work.

Keep me abreast, but you need to hold yourself accountable.

In addition, pick 1-2 personal goals (outside of work) you want to achieve on a weekly basis.

Share these with the team in a transparent fashion.

As a team, we hold each other accountable. The consequences are self-enforced.

“Call your shot” is another way we’ve phrased this in the past, which makes the balance of “bottom-up” vs. “top-down” much more enticing, digestible, competitive and fun.

While this ‘corporate’ philosophy might appear far-off from running, I utilize the same technique during my training. I have a coach who holds me accountable with a training plan, but I take responsibility if I miss a run, or conversely, if I have a stellar workout. Failure or success is the product of a mindset with extreme ownership.

Now, stop. Think, for a moment: When was the last time you started something, and genuinely had no idea if you will be able to complete it? Many people do the same tasks every day, go to the same supermarket, watch the same TV shows, see the same friends and go to the same restaurants. To me, running 100 miles is a commitment to develop a new routine where consistency is pushed to its brink. As ultrarunners, we first commit—not to finishing—but to toeing the line.

We start running 100 miles the second we start training, and training starts when we make a commitment to ourselves. It’s a recurring cycle that leads back to the simplest beginning: Commit, hold yourself accountable, and run. A lot.

WHY JAVELINA?

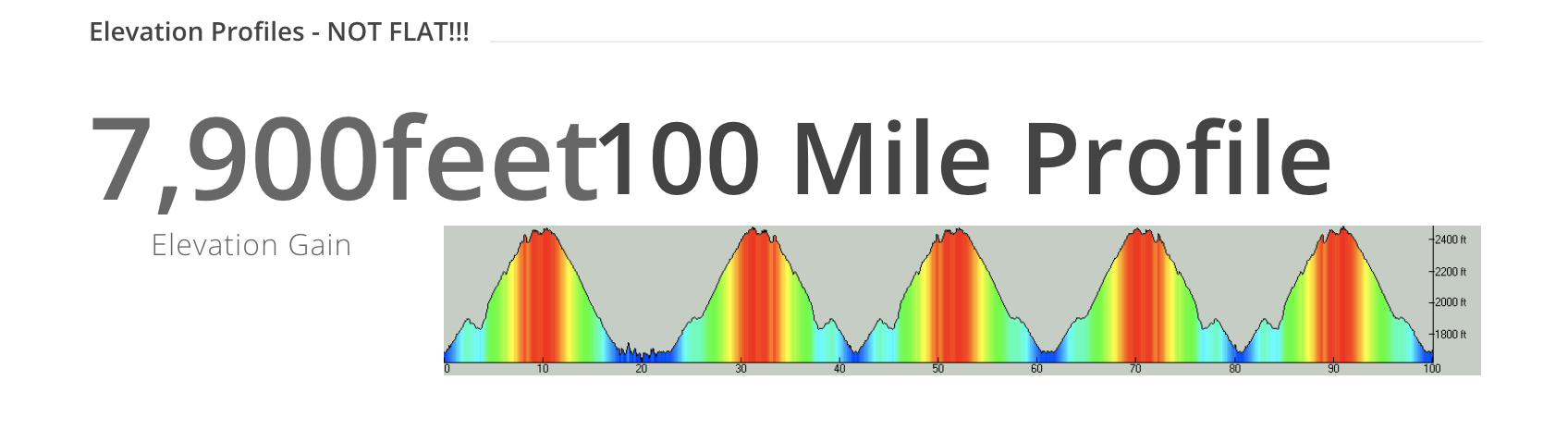

I ended up choosing The Javelina Jundred (pronounced hav-el-ina hun-dred) mainly for the course. Javelina is a looped 20-mile course in Fountain Hills, Arizona, USA, with a total of 7,900 feet of elevation gain, and 7,900 feet of descent. While I’d love to run some of the larger, iconic, European ultras and 100-mile races (e.g. UTMB, Mozart 100, CCC, Lavaredo), they are all in the Alps or Pyrenees and require a ton of elevation training. This year I also dreamed of attempting some of the iconic U.S. 100-mile mountain races (Western States, Leadville) although they are also very hilly and have competitive lottery entry rules (I didn’t get into WSER in 2019 via the lottery, but just qualified again for the 2020 lottery with my finish at Javelina).

All these courses sound great, and certainly look incredible when I scroll through Instagram while quickly shoveling granola in my mouth every morning…but the reality is that I currently live in Amsterdam, which changes my prospective race schedule. A fun fact for those that don’t know: The Netherlands is the flattest country in the world! This makes training for any ultra a bit more challenging, specifically ones with any climbing involved.

Amsterdam does not provide a single hill or mountain. The biggest “incline” is the man-made NEMO Science Museum in central Amsterdam, with a staircase totaling a whopping 68ft of elevation gain. But, there’s a gate half-way up until the museum opens, so weekday hills before work are not possible. Outside the city, the closest hills are 1.5+ hours away, and a plane ticket is needed for to explore any true “mountains.”

To be clear, I sincerely adore Amsterdam and love living here, but mountain running is unfortunately not one of its perks.

NEMO Science Museum in central Amsterdam, a 68-foot incline where I did a lot of “hill” repeats.

After racing the Vermont 100 last summer (17,000 feet of gain) I learned the importance of finding a hill, making friends with it, then becoming truly intimate, getting to know every single crack on its face. In many ways, this is the saga of the life of ultra: the runner & the mountain. It’s a battle (which the mountain often wins).

So, I quickly gave up hope of registering for an iconic mountain ultra, at least in 2019. However, when I started to research “flat” hundred mile races, the list became quite limited. After all, the most attractive part about running 100 miles is playing in the mountains! I debated registering for Tunnel Hill 100 in Illinois, USA, for awhile, but landed on Javelina as it like a good combination of manageable vert of 7,700 ft, while also offering a fun race atmosphere…

Indeed, Javelina is known as the “biggest Halloween party in the desert”. The people at Aravaipa Running, the company who puts the race on, do an outstanding job striking a balance between a competitive endurance event and a festive party.

The only way I can describe it to people who haven’t been there, is a combination of a multi-day running event, mixed with the Burning Man festival, a big disco party, a college Halloween rave, a family campground, along with a couple flavors from your local pizza shop & tattoo parlor—all meshed together in the middle of a parking lot outside of Flagstaff, Arizona. Yeah, it’s pretty insane.

Notable awards aside from top male and female finishers include “best costume” and “best ass” for runners who dressed up for their 100 mile runs, my favorites included a man in a full suit at an aid station offering tequila and beer.

Source: Chris Worden

With all festivities aside, The Javelina Jundred is not a course to be taken lightly. The detailed Runners Handbook warns of its subtle challenges. The course usually claims around a 50% of runners as DNF’s (did not finish) — this year 54% did not finish. Despite being one of the “easier” 100-mile courses, it has one of the lowest finish-rates. Ultimately, the heat is not something to take lightly. Getting up to 95 degrees fahrenheit / 35 degrees celcius is not something to gloss-over. Also, the 8,000 feet of climbing/descent is something that can become problematic if not appropriately trained for.

TRAINING

I raced less in 2019 than I have in recent years because I was more focused on moving and settling into my new home: Amsterdam! I moved to Amsterdam in March for work with FareHarbor. After moving, I ran the Jurrassic Coast Challenge in May, a 58K ultra along the UK’s beautiful southern coastline.

Over the next few months I built a solid base of fitness without any injury. I ran 5-6 days per week with 1-2 hard workouts, building longer mileage on the weekends. Nearly all my early training was flat, while the weather was warm and the days were long. I did a few marathon+ runs to the beach from Amsterdam, where I’d meet Lucy and take the train back home.

In June, I did did a local 25K race in The Netherlands, which gave me knowledge of the closest “trails” to Amsterdam, about a a 90 minute train ride. There are plenty of beautiful paved bike paths in The Netherlands, but many people don’t know about the hidden “trails”, many of them covered in sand. This started getting my legs accustomed to the rolling desert hills that I’d encounter at Javelina.

Many of my morning runs consisted of an out-and-back ~8-mile run through Westerpark. This route offers a nice 3-mile stretch of park running toward the Western edge of the city, then curling back to watch the sunrise creep over the canals. Some mornings I’d weave and wave hello to partygoers who were leaving a rave in Westerpark at 6am, shuffling on the running path; they looked like a mob of slow-moving, drunken tranquil zombies as my headlamp bopped between them.

I wanted to run 50-miles in a single run before Javelina to prepare mentally. While it’s perfectly possible to have a good training period with ‘longest runs’ as two back-to-back 30-35 mile days, however I wanted to hit the 50-mile mark from a mental perspective. It had been awhile since I covered that distance. So, in early September, I went out for a 50-mile run in the National Park Veluwezoom near Arnhem, and ended up stopping after 43 miles. I had enough and didn’t want to force injury, but I was satisfied. The next weekend I did some big-mountain running near Halstaat, Austria climbing over 10,000 feet in the Alps. While this wasn’t race-specific, it got my legs ready and mind right.

Ultimately, hills and heat were my weakness heading into training, and I knew I’d need to get a little creative to prepare. About 2 months before Javelina I knew it was time to start to think more seriously about vert and heat training. This meant joining a gym.

Since Javelina does not have extreme inclines and declines, my training would need to range on modest grades from -2% to +2%. While many modern treadmills have a “decline” function, I struggled to find this in Amsterdam. I called/visited a total of 10 fitness gyms before finally finding a treadmill that was able to decline -3%, so I could properly beat-up my quads. The game was on.

“THE treadmill” I got to know very well during this training block…

As the race neared closer, my treadmill runs got longer with more heat layers. I would commonly wear a long-sleeve base-layer, hat, gloves, and a winter jacket on the treadmill to keep the heat in. Then, immediately after my treadmill workout, I’d hop into the sauna and sweat for 15-30 minutes. This was tough. If you’ve ever been in a sauna and reached the “limit” of needing to get out—try sitting for 5 more minutes. I genuinely found some of my sauna sessions more difficult training than the actual training runs.

The final few weekends I was logging about 20-26 miles on the treadmill with long climbs/descents, followed by another run on Sunday, for a total of 70-80 miles in the week. While this was a bit boring, it did prepare me well for the specificity of the Javelina course.

INJURY STRIKES (AGAIN)

Twenty-one days before the race I was doing one of my final speed workouts on a treadmill. The workout was an 8-mile progression run on 2% incline, starting at 7:05 minute/mile pace and ramping to 5:50 minute/mile (5k pace). Towards the end of the run I increased the speed and immediately felt a pull in my hipflexor.

Over the next few days, the pain moved from my hip to my gluteus medius, which felt like a big, frosty snowcone. I kept pressing with my fist against my glutes trying to get it to melt away. It didn’t.

The next week the pain shifted from my gluteus to my groin, where it stayed until race day. The pain became less “sharp” and turned into general discomfort.

With every step, a little devil was plucking at my groin like a harpstring. Pluck, pluck, pluck with every step.

I stretched, iced, rolled and shouted with frustration. I mostly rested and tried to stay positive. I was going to toe the start-line, I just didn’t know how I’d fair or how far I’d make it.

For those that read my Vermont 100 report, you’ll remember a very similar injury happened in the same spot, at the same time during my training. The disheartening part is that I focused on hip-strengthening, flexibility, and band-work throughout my training, but clearly not enough. I definitely have a weakness with my right hip that I’ll continue to work on.

Message to my brother 2.5 weeks before the race

Message to my pacer, Ben, 1.5 weeks before the race.

RACE COURSE

As you can see with the elevation profile below, the first ten miles of each loop is “uphill” and the second ten miles are “downhill”. I put these in quotations because the climbs are gradual, and actually look “flat” from first glance. However, runners beware: this course is not flat and the inclines/declines will deteriorate your running-gate as the miles pile-on.

The course is “washing machine” style, meaning runners change directions on the course every loop. This means the course does not get as boring, and also allows you to see the race leaders several times throughout the race. As a fan of ultrarunning, it was cool to run by elites like Patrick Reagan (1st place overall in 13:11) and Kaci Lickteig (1st place female in 15:32).

The start of each loop is the Javelina Jeadquarters where my crew was stationed throughout the day with a pop-up canopy tent. The Jeadquarters is a vibrant scene with pizza cooking all day, beer pong tournaments for crews, and lots of runners coming in-and-out of their loops.

There are a total of 3 aid stations along the course: Coyote Camp, Jackass Junction, and Rattlesnake. The halfway point of each loop is Jackass Junction, the largest aid station that is is fully equipped with a dance floor, disco ball, a DJ, dancing volunteers and hard-alcohol (if you’re interested late in the race). A big party!

Javelina is a looped 20-mile course.

Source: https://aravaiparunning.com/network/javelinajundred/race-info/

While the course is known for being runnable, it is certainly not flat!

Source: https://aravaiparunning.com/network/javelinajundred/race-info/

Strava link below (watch died at mile 90):

RACE DAY

I arrived in Arizona five days early to acclimate to the heat and adjust to the time zone. This gave me ample time to familiarize myself with the course and get my gear organized. I was able to run two different sections of the course, get a lot of work done remotely, and eat a lot of potato salad. Note: There are not a lot of food options in Fountain Hills, Arizona other than McDonalds, Burger King, Wendy’s, and the supermarket.

With the race starting Saturday morning at 6am, my crew arrived on Thursday evening with big smiles, lots of positivity, and a few outrageous moustaches. While a lot of my thoughts were focused on my hip, my crew helped put my mind at ease and remind me that I was lucky to have a strong support team. With some pizza as a final meal on Friday night, we were ready to go.

The best crew at Javelina! From left to right: Ben, Shelby, Nolan, Jamie, Joe, Chuck!

Shelby paced me miles 60-80, and Ben 80-100.

On Saturday morning, Shelby and Ben accompanied me to the start-line at 5am. It was a PARTY. This was one of the coolest pre-race experiences I’ve ever been part of. There were fire-dancers, loud music and dance parties — the playlist was epic. The sun hadn’t even come up and nobody was running yet, but the adrenaline was flowing.

At 6am we began the journey. Within a few minutes, cheers from the Javelina Headquarters faded behind us, as we plunged into the desert darkness. Nobody said much for the first few miles, just deep breathing. The laser focus needed for the hours ahead was palpable.

I wrote my two mottos on my water bottle:

BALANCE: Be a leader and never conceit, ever • . TYT: Trust your training

Loops 1-2:

The first two loops went according plan. I tried to be as conservative as possible because I knew that many people would go out too-fast. I was in about 40th position after the first 20 miles and I knew that many runners ahead would fade later in the race.

I was trying to keep my pace around or over 10 minutes/mile, but I ended up closer to 9:30 - 9:40’s. While this may seem slow, a 10:00/mile average pace equates to a 16:40:00 100-mile run, which is an elite/professional level that only around 5 runners in the whole race would achieve. With that said, I also knew the first two loops would be easier because the the heat was manageable (certainly in the dark on the first loop). So, pacing was okay, but I know I could have been even more conservative. This is definitely a race where many runners fade after loop 3 (60 miles).

As I finished the second loop, I was running with a newfound friend named Pat from Oakland, California, whom I met on the course. We exchanged stories which helped the miles pass by. I think we ended up running 20-25 miles together.

40 miles done, getting ready to start loop 3. Nolan on my crew is putting ice in my hat.

Ice in neck bandana, ice in my hat, sponge-down, sunscreen, sun-hat…bring on the heat!

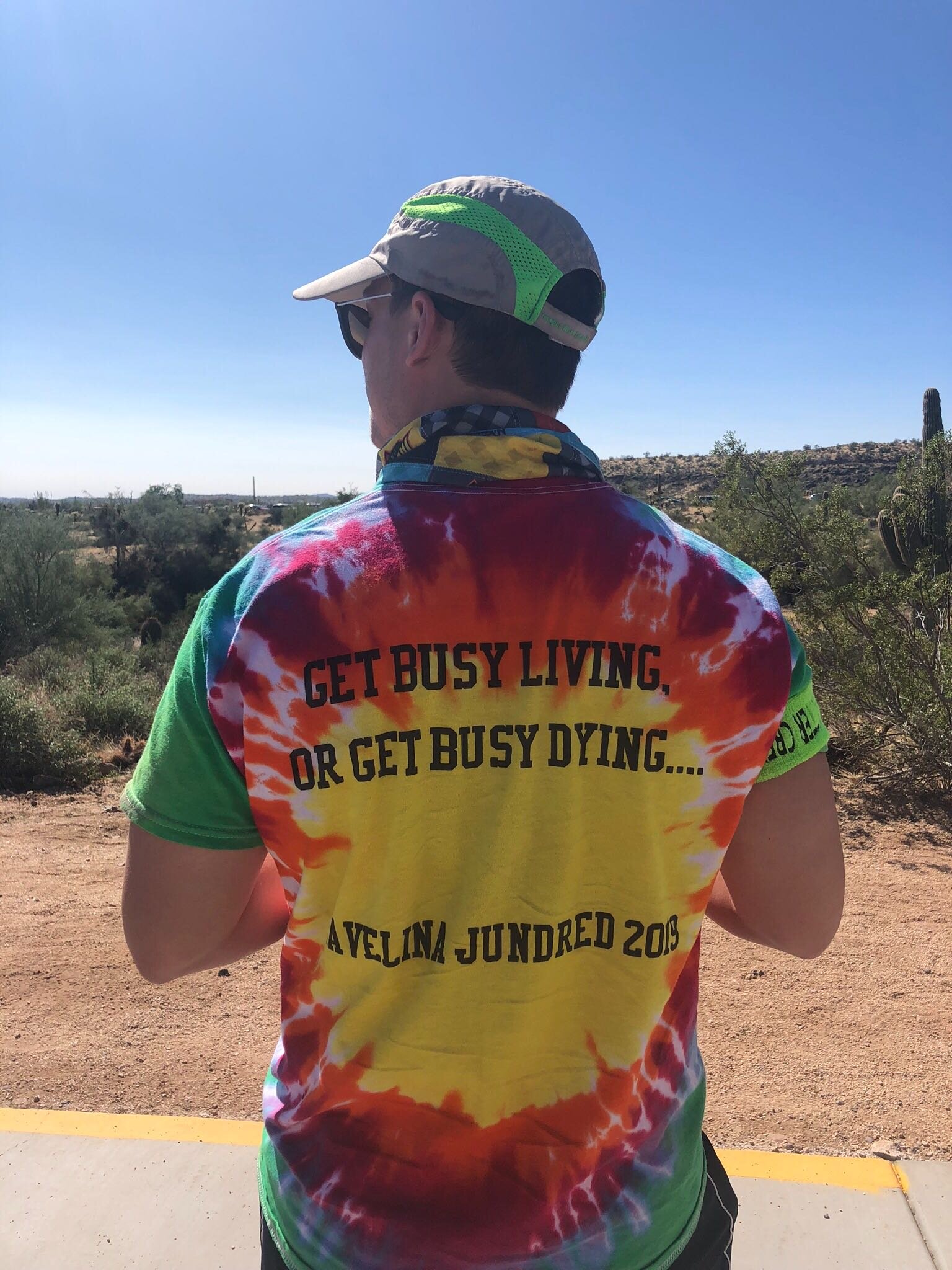

The shirts my crew surprised me with.

“Get busy living, or get busy dying…” -Andy Dufresne from The Shawshank Redemption

Loop 3:

Hot, hot, hot! This was the theme of this loop. With 40 miles under my belt, my legs were starting to feel the distance. It was now about 1pm and the sun was at its peak. In addition, the steepest and most technical part of the trail is the clockwise ascent from Javelina Jeadquarters to Jackass Junction. This section from miles 40-50 were my lowest-point and most difficult of the race.

At this point, I was drinking over 30oz of water per hour and trying to keep my body temperature as cool as possible. I covered my head and neck with ice with every opportunity, and I was topically spraying ice-water on myself that dried within 10 minutes. When I reached mile 45, I “let” Pat run ahead of me (actually, he dropped me) as I slowed down in attempt to bring things under control. As my body temperature escalated, I could feel my heartrate spiking. Physically, I was starting to panic a bit and lose control. I knew I needed to surrender to what was coming my way, it was only a moment and it would pass eventually. I remembered my motto: trust your training, and recalled the countless hours spent in the sauna preparing for this exact moment.

As I arrived at Jackass Junction at mile 50, I dunked my face in cold ice-water and squeezed a sponge over my head three times. I exhaled with relief as my body temperature leveled itself. I grabbed six pieces of watermelon, a few fist-fulls of potatoes with salt, and a three handfuls of gummy worms.

I was halfway done. Mentally, I wasn’t great. Physically, I knew that I needed one thing: the sun to go down. If heat could be removed from this equation, I knew I’d be able to increase my pace again and move faster. I looked at my watch: 3:30pm. I knew I had about 1.5 more hours of heat until the sun would start to set and cool-off. So, I did what I do best: run.

I ran toward the Jeadquarters in ran towards the night. I ran to my sister, Shelby, who would be picking me up at mile 60. Those next 10 miles I took in another ~60oz of water and urinated twice. My hydration was solid and I knew that soon I’d be able to spend less mental energy worrying about my liquid and salt intake. I ran towards darkness, shuffling along, nodding at each cactus I passed.

Finally, I felt a whisp of wind at my back and saw the sun begin to drop. As I rolled-into the Jeadquarters at mile 60 I was burnt, but not broken. The heat was gone and I was ready for darkness once again.

Finishing loop 3, 62 miles done! Smiling…or hurting? Both!

Loops 4-5

Shelby and I grabbed our headlamps and went off in the desert. The next 10-15 miles were really awesome. The desert glowed orange as the sun dropped beneath the distant mountains. We could hear some snakes scurrying in the sand around us and even ran over a massive tarantula.

Enjoying the sunset around mile 65. Preparing for darkness.

On the climb up to Jackass Junction, synced-up with another runner named Tony who I had been running with earlier. Together, we laid-down down the hammer and started playing pac-man, picking people off one-by-one. We probably passed 10-15 runners on the way up to Jackass. When we reached Jackass there was a big party happening. I danced for about 5 seconds, slammed a cup of vegetarian noodles, and ate more watermelon. Then, we started on the descent back to the Jeadquarters. Once more, we were blazing past another 5-10 runners. My sister took the lead on the downhill, followed by Tony and then me. We crushed several sub-9:30 miles en route to Coyote Camp aid station. Feeling good!

As we neared mile 80 and once again the Javelina Jeadquarters, I was feeling strong, but needed caffeine. I had avoided any caffeinated gels until this point, and I could tell I was slurring my words and wanting to close my eyes. As we approached the Jeadquarters, Shelby ran ahead and alerted my crew that I was in good spirits, but needed two things: my toothbrush and a cup of coffee.

The final pit-stop at mile 80 was pretty quick; I am happy to say that I didn’t sit once during the whole race. I brushed my teeth, drank two cups of coffee, some Powerade, and set-off with my friend Ben who’d pace me the final 20.

I continued my strong running from miles 80-90, in pursuit to my final stop at Jackass. I was moving slower, but still managing to mostly run and kept moving as fast as my legs allowed. I wasn’t passing as many people, but I was sitting in somewhere around 12th male overall.

Then, things started to fall apart. After Jackass at mile 90, my left ankle started swelling considerably, making it painful to run. I think this was partially because my right hip was injured, and I was over-compensating with my left leg, which put pressure on my ankle. In addition, I hadn’t considered how much relatively “flat” running would wear on specific muscles over the course of 18+ hours of running. I realized that my calves and glutes were not fatigued or sore at all, while my quads and ankles were completely trashed.

My pacer Ben was doing a great job encouraging me to run and trying to get me to ignore the pain in my ankle.

He’d shout, “one, two, three, go!” and I’d try to lift my legs and go into a jogging motion. Nothing happened. I started getting passed by many runners and it was now below 45 degrees farenheit and I was shivering. I didn’t have any gloves, so I stumbled along the trail with my hands in my shorts. This section was demoralizing and sobering.

I walked from miles 90-95, which was truly disappointing. Mentally I was ready to run, but my ankle was telling me otherwise. With every step I was limping on my left leg with a slow drag of my right foot. I prepared myself for another 1.5-2 hours of “walking it in", until something shifted in my mind. I knew if I started running I could be done in under an hour. One hour? I can do that. I can do it.

Out of nowhere, I picked up my feet and started jogging. I blocked he pain out and suddenly I was moving, my hands were warm, and I was just running with a friend in the middle of the night.

I didn’t stop until I hit the finish line.

It’s truly incredibly what the mind is capable of. I had been walking for over 2 hours straight, completely dejected and fatigued from 95 miles of physical exertion.

Then, in a second, it all changed.

I thought about the commitment I made to toeing the line, and I thought about the accountability zone. I thought about how much time I put into this. I thought about how grateful I was for the support around me, for my friends and family. After all, running isn’t everything, and it’s what we leave behind that carries a bigger impact.

But, in that moment, I was committed to running again. I picked up my feet. I ran and didn’t stop until I finished what I started, holding myself accountable.

Overall Stats

Time - 20:14:46

Overall - 35

Men - 27

Finish!

THANK YOU!

After my Vermont 100 last year, I wrote the following:

Running 100 miles is not a single-day accomplishment. Instead, a 100 mile feat is the product of a lifetime of experience, melded into a singular, focused determination. It’s 6+ months of physical discipline and a well-executed nutrition/hydration plan. It’s a the culmination of everyday, showcased in one.

I think this statement still rings true, and I believe it even more. You can’t run 100 miles without a strong support system who understands the commitment you make, and hold you accountable for getting there. I’m incredibly grateful for the encouragement around me, both personally and professionally. Whether it’s words of encouragement, or understanding why I need to say “no” to a night-out, or even a post-training massage — there is a lot that goes into it. I thought about all these people during my run, and deeply appreciate their commitment to my goal.

The list is long, but Lucy and my family are at the top of the list. They held me accountable and pushed me to reach new limits. I also the best crew at the whole Javelina Jeadquarters! Only true, dedicated friends are willing to sit in the desert heat for multiple days with no sleep, just to see you run in circles. They were committed and I appreciate that. Thank you to my amazing friends at FareHarbor for bringing dedication and energy to work everyday. I am motivated and inspired by many of my coworkers who are deeply committed to their work, and what we are building. Thanks to my coach @runfastah who held me accountable and ensured I was prepared, but understands there’s more to life than running. Thanks, Scott! Lastly - my PT, Pieter in Amsterdam at Gustav Physio also helped me deal with my hip injury. If you’re looking for a PT in Amsterdam, I highly recommend.

FOOD

I tell many people that running 100 miles is as much an eating competition as it is running. In order to run a successful race, you need to be a tactician about calories and food, especially in the heat. Think about it this way: if your legs hurt, you can push through. If you don’t have enough energy or are dehydrated, you’re screwed. There is no bouncing back.

My plan was about 150 calories per hour. During the daytime I ended up closer to 200-220 per hour because of the heat. This is probably the most I’ve consumed during any ultra. My stomach held up fine, I had no nausea or gastro issues.

My crew did a great job at laying out all my food so I was ready when I came through the Javelina Jeadquarters.

Total consumption:

15 chocolate Clif gels

5 handfuls of gummy-worms

1 pack of skittles

2 handfuls of avocado

8+ handfuls of potatoes with salt

15+ slices of watermelon

10+ orange slices

1 cup of veggie noodles

2 cups of veggie soup broth

3 packs of Honey Stinger chews

1 Gu Stroopwaffel

3 slices of vegan pizza

1 hummus pita wrap

3 cups of mountain dew

3 cups of coffee

Water/Electrolyte intake:

~20-32oz of water per hour

1-2 electrolyte supplements per hour

Due to the heat, I ended up consuming more water during the day than I had planned. From miles 20-60 I was averaging about 30oz of water per hour, along with 1 Nuun electrolyte tablet and 1 condensed salt pill. My original plan was 22oz with 1 electrolyte tablet.

My consumption caused me to urinate every ~3 hours, which was exactly what I was hoping for. Once the sun set, I was less disciplined about water intake, as dehydration concern was less of a factor.

Gear:

Headlamp: Petzl Reaktik (300 lumens)

Socks: Injinji

Shoes: Altra Lone Peak 4.0

Gaiters: Innov-8 All Terrain

Shorts: Patagonia

Sunglasses: Oakley

Sun Hat for daytime: Outdoor Research

Regular Hat for nighttime: Headsweats

Hydration: Double Nathan 22oz non-grip

Patagonia Houdidni windbreaker

Nike singlet

Tired legs & lots of gratitude!

5am, a few hours after finishing. Enjoying some pancakes, watching the sunrise, and cheering runners on. Life is good!

Some much needed runner & pacer bonding/sleeping after the race.