Ultra Pad Netherland (UPNL) FKT (June 2020)

Scop-Swishh-Wishh; Scop-Swishh-Wishh

This was my metronome.

It was 4:30am. Darkness engulfed everything around me. Aside from a few hooting owls and screeches from animals scurrying over branches, all I could hear was the repeating scop-swishh-wishh from water I carried on my back. The water jumped like a giddy kid, but the sound ringed with intimidation from my ears to chest.

How long would my mind fixate on this sound? I was trying to stay calm and focused. There was a long day ahead.

The sound continued. Scop-Swishh-Wishh; Scop-Swish-Wishh.

I ran.

Looking back a few months, I never stopped running.

When a crisis hits, there are two options:

1. Become a winter frog and go into hibernation

2. Become a summer frog and play on lily pads

A frog hibernating for the winter.

Frogs in the summer, hopping from pad to pad.

There are times for both. Depending on the situation, there are moments to conserve and retreat. There are also times to get out, adventure, and explore. While these scenarios my appear contrasting, they are, in fact, harmonious. It’s a delicate balance, but sometimes, you can do both. Hibernate in some areas, get out in others.

For many, the word “COVID” has been synonymous with hibernation. Since February, much of the world has been in a sate of hibernation—and rightly so. Many businesses have hibernated to stay afloat and preserve cash. We’ve been physically hibernating from other people. Those who have gotten ill have been hibernating for their health, and to protect others. These are all musts—the right thing. Hibernation is not “fun”. Enticing weekend activities are no more. The economy essentially shut down. Many have lost their jobs. Many have lost their lives.

A crisis puts extreme clarity on what’s important. It underscores Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, putting survival, family—whatever you cherish most at the foundation. You sacrifice the rest, simply because there is no other choice. You let it drop, perhaps never to be picked-up. And that’s okay.

So yes, sometimes there is no option, other than hibernation. Crises can strip us of choice. This is among many tragedies. However, for some, options do remain. It’s the things we refuse to sacrifice which we cherish most. Personally, I’ve been lucky to have choice in my life over the past few months. I’ve had the choice to become a summer frog, even in the “winter”—a time for hibernation.

I have certainly hibernated in some facets of my life. Socially, I’ve hibernated, and haven’t seen friends as often. I’ve stayed-put without travel, and even hibernated at work—focusing on core projects while de-prioritizing non-essential tasks. I’ve focused on cooking good food and having quality conversations. I’ve planned trips for when hibernation is over.

In other ways, I’ve continued to be a summer frog. Time has been a gift for many, including myself. More time with family, whether in-person or via video. Many have taken the opportunity of time to go through old photos, learn a new skill, or finally catch-up on stack of book recommendations that’s been growing for years. It’s time to get caught up. To slow down. Many have taken the time to protest, speak-up, write, or maybe just think a little more, or a little harder to make sense of it all. It’s the things we take on during a crisis that build resilience.

For me, running was something I never sacrificed. I kept going, kept running—leaping from lily pad to lily pad—exploring new things.

Fastest Known Time

What is an FKT?

I was originally planning on running the San Diego 100 on June 5th, which was cancelled due to COVID-19.

When the race was cancelled, I was deep into my training, and as such, I started looking for alternative running endeavors I could compete in—while keeping a social distance. An FKT stands for a “Fastest Known Time”. Fastestknowntime.com offers a wide variety of routes, from highly trafficked and competitive thru-hikes like the Appalachian Trail and the Nolan’s 14, to less-popular, shorter routes submitted every day. If you’re looking to learn more about how FKT’s were developed, you can read this article about Buzz Burrell (the founder), and tune into the Fastest Known Time podcast. Buzz is a great personality and ambassador within the sport of ultrarunning and has many impressive FKT’s to his name.

The Ultra Pad Netherland (UPNL) attracted me for a few specific reasons. First, the course ventures through three different national parks in the Netherlands and has a diverse offering of terrain and views. Second, the start-line is a 40-minute drive from where I live in Amsterdam. This made it easy logistically, and I didn’t have to travel to another country with borders closed. Lastly, in April I ran 50 miles on a training run, and it happened to cover parts of the UPNL course on my self-designed route. So, I was familiar with the beauty of the course, and knowing the twists & turns is always an added advantage.

Why attempt an FKT?

There are no screaming masses of fans at an FKT, no fancy start-lines with music, no robust aid stations, and certainly no festive beer tents. There are no sponsors, free swag, medals or trophies. There are no warm-up sessions with other runners, gear chat, friendly banter, or shared, communal suffering. There is no physical competition around you. Only the ghost of the Fastest Known Time.

The FKT is one of the purest experiences within the world of running, which attracted me. There is something exciting about waking up on a typical day and accomplishing something that no other human is attempting. It’s just you, and it all begins with the click of a watch. Then you’re off. Alone.

To navigate an FKT route, you do so yourself. This is commonly done by using a map, compass, or GPX file on a watch, phone, or some other device. Some FKT routes are marked trails; other routes, like the UPNL, are unmarked trails, or a combination of several trail systems, and therefore anyone attempting needs to use GPX to navigate. This added to the adventure, but also created room for error, which adds time. Every wrong turn (there were many) adds precious seconds to the ceaseless clock.

The Fastest Known Time of the UPNL was 20 hours and 59 minutes. I finished the route in 19 hours and 19 minutes.

There are a few unique pieces of the FKT format that I’ll reflect on here:

First, is there is a binary success/failure of the attempt. You either succeed, or you don’t. You either win or you lose. In a typical race, you have several goals, which could be based on time, position/rank, etc., and they can adjust throughout the race. For example, if you’re feeling poorly, maybe you try to beat the runner alongside you. Maybe you try to come in “top 20” instead of “top 10”. With an FKT, there are arguably no alternative options for success. Note: this depends on your goals heading-in, and depending on the individual, some FKT’s could be more relaxed or not an “A” goal to break the record, but rather just attempt it.

There is little to no external stimulus. Instead of running past other runners, I was running past a family out for a Saturday afternoon mountain bike ride. This is not nearly as motivating. While I typically don’t see myself as a runner that heavily relies on stimulation, I realized how much it can help. Going into the run, I decided I would not listen to music until mile 50, which would give me a ‘reward’, or something to look forward to. I followed this plan. When I plugged music in, it did give me a nice distraction and boost.

There is nobody to blame but yourself. There is full ownership and accountability with an FKT attempt. Make a wrong turn? Your fault. Screw up hydration? Your fault. Forget to pack something? Your fault.

While runners don’t consciously place blame on other people, it’s easy to say “oh the race director said they would have mountain dew at the aid station, but they didn’t”. Or, “my crew forgot to bring clean socks”. I think doing this FKT attempt made me more self-reliant and accountable as an athlete and runner. There is nobody to point the finger at.

The Route

The Ultra Pad Netherland (UPNL) trail is a 154.5km (96 mile) route with 3,500 feet of elevation gain. It connects three different national parks: the Utrechtse Heuvelrug, the National Park Veluwezoom, and the National Park Hogue Veluwe. All three of these different parks have distinct landscapes, flora and fauna.

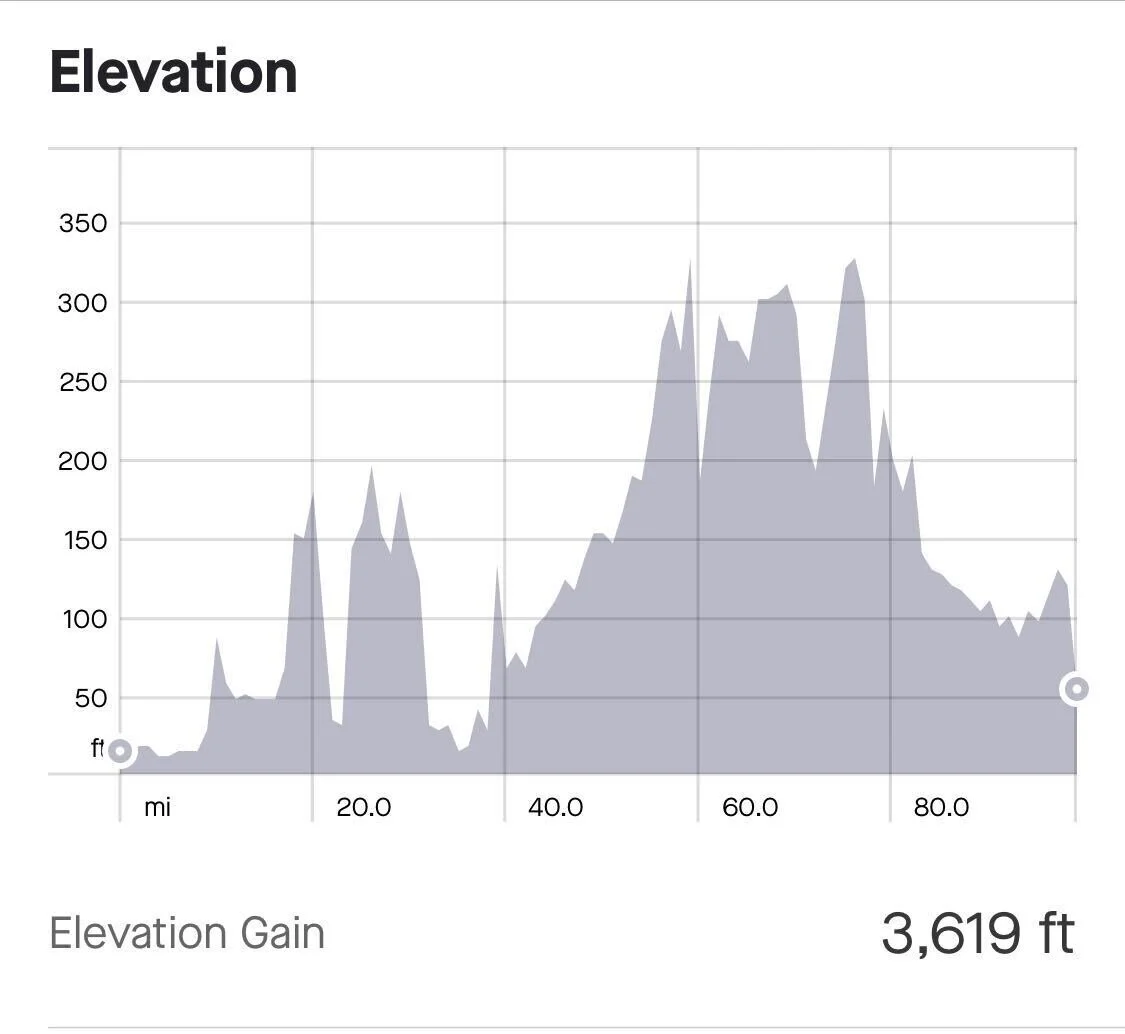

Here is the original GPX file if you’re looking to attempt it. According to my Strava, I covered 99.4 miles with 3,619 feet of gain.

Notably, the UPNL is designed to be run specifically on June 21st, the summer solstice. With a “race track” format, you’re supposed to start at sunrise (5:18am) and stop a sunset (10:06pm), which provides 16 hours and 48 minutes to get as far as you can on the course (this does not include twilight hours - it is indeed “light” for significantly longer than 16 hours). Why this structure? It’s actually illegal to be in the woods after 10pm in the Netherlands, in order to give animals time to sleep, as I’ve been told.

I did not participate in this format for a few reasons. Frankly, I didn’t want to wait until June 21st to run the UPNL, and also figured I wouldn’t be running in the dark too long, since I was targeting a sub-20 hour finish. With twilight light, this meant only running in actual darkness for an hour or two. There have also been a number of other people who have run the course during the night. I was not the first. The previous record holder, Jaco de Ruiter, ran the course in the dark, as did the record-holder before him. However, I would encourage anyone thinking about running this course to take this into consideration. As an ex-pat, I’m not totally privy to these forest park laws. As the sun was setting around 9pm on the course, I ran into a hiker who was concerned he’d get a €400 ticket from the forest police for staying out past 10pm, which caused a downward spiral of negative thoughts in my own head. I never saw any police.

The UPNL starts and finishes at train stations: The Hilversum Sportpark Station and the Wezep Station. These are the official “start” and “finish” lines of the route, however you can choose to run in whichever direction you prefer.

I decided to start in Hilversum and run to Wezep, although the previous FKT attempts were done in the opposite direction. My reasoning is simple: I was more familiar with that direction, and had run several miles on the route, heading East, away from Amsterdam. This meant that the “hills” would come later in the day (see elevation profile below), although the gains are quite modest.

The course is quite flat for a 100-mile course. The Netherlands is not home to many hills. While this made it “easier”, I prefer more climbing. The few hills offered reprieve to the same muscle groups that were taking a beating all day: my ankles, knees and quads. Hills not only give you variety of terrain, but also allow your glutes & lower-back to absorb more stress.

Elevation profile of the UPNL. While it looks hilly in the latter half, the grade is never steeper than 3%, which makes the climbs manageable. The Netherlands does not offer many hills, so this course is quite flat.

Preparation:

There are several types of FKT’s you can attempt: Supported, Self-Supported, or Unsupported. Each category has its own record for each individual route. You can read about the specifics differences on the FKT site, but I opted for Self-Supported. This means that nobody could aid or assist me during my run. I had to support myself.

Navigation was a big piece of this preparation. Since I only had about five weeks to prepare for this specific run, I took a few trips out to the course, and was able to cover about 50 miles of terrain. While this helped, I still got lost several times on the parts I did not cover beforehand. If I had more time to prepare, I would have tried to cover the whole course beforehand, although this is hard to do without a car. Some areas are not near a train station.

The biggest challenge within the self-supported category is food and water. There are no rivers along the UPNL course, so I couldn’t fill-up water naturally along the way. There are a few gas stations and supermarkets near the course, although none are directly on it. While I could have planned to detour from the course to resupply for food and water, I knew this would cost valuable time. As such, I decided the best way to support myself with food and water would be to bury bags along the course before I started.

I identified 10 “aid stations” on along the course where I’d drop supplies. These were at, or nearby, a road crossing so it was accessible to drop supplies in a car during the day(s) prior. While some of the trail is fairly remote, it wasn’t too difficult to find places near a road.

An added bonus to this method, was I broke the race down into segments. This was a major mental win. Since there were no predefined aid stations, landmarks, or mountain peaks, I created my own “milestones”:

On Thursday before the run, I organized drop-bags to bury at the stops outlined above. Here is what it looked like:

Then, I tagged the trees of where I buried the bags. This ribbon is also glow-in-the-dark so it’d be able to reflect at night. Note: it took me over a month to find this ribbon since everywhere is sold out from COVID-19.

Luckily, no animals found the bags I hid.

Run Recap:

If this run were a book, the first chapter would be titled “Urination”.

Scop-Swishh-Wishh; Scop-Swish-Wishh.

I was carrying a lot of water. Within the first three hours of my run I urinated nine times. Yes, you read that correctly: nine times. While it ended up being a hot day (76°F / 24.4°C) I hydrated too much, too early. I was consuming 22oz / 600ml of water in those hours, not including water and coffee before I started. The temperature in the Netherlands doesn’t truly warm-up until after 12pm and the mornings are chilly. In the first hours of the run, I was hydrating as though it was already the heat-of-the-day, although it was still cool. Since I wasn’t sweating, my body needed to unload this liquid by urinating.

This was not ideal, and caused me to worry about hypnotremia (over-hydration) which is one of the most common reasons for ultrarunning DNF’s. Hypnotremia occurs when you drink too much fluid, and essentially cause your organs to ‘drown’ and cells to swell, and your kidneys are unable to dump-out the excess fluid. Since I was still urinating, albeit too often, I was comforted that I was still getting rid of excess liquid. However, I knew this wasn’t sustainable.

I slowed my fluid intake significantly between hours 3-6 of the run, until it got hot, when I started sweating more. To give context to how quickly the hydration spectrum can swing, 10 hours into the run my urine was as gold as The Queen’s crown (not good). Things can change very quickly, and you need to stay acutely in-tune to what is happening in your body.

In addition to over-hydrating early-on, I also struggled with nausea from caloric intake. One strategy I discussed with my coach was ‘getting ahead’ with calories early in the run. This is a common strategy, because if you get behind on calories it’s hard to play catch-up. If you’re behind, you’re too late. As such, I was consuming over 200-250 calories per hour in the first three hours of the run. This is a slightly higher volume than I trained with, and caused me to struggle digesting all those calories at once. This caused nausea, which makes you want to eat even less. This is a very common cycle in ultraunning (too many calories → gut can’t digest → nausea → can’t eat → can’t run → drop out).

I wanted to avoid this cycle, so I slowed my pace slightly, hoping to allow myself to spend more energy on digestion opposed to running. I also took one pepto bismol I was carrying. This worked well, and after two hours at a slightly slower pace, I was hit with a wave of hunger (good sign) and was eager to eat more, and move faster.

If anyone is looking for a good listen on this topic of caloric intake & ultrarunning, I highly recommend this podcast episode with Jason Koop and Nick Tiller.

Looking back, I should have trained with a higher caloric intake to “train my gut” to handle 200-250+ calories per hour. This is a common practice and I could have done a better job focusing on this during training. It is sometimes a strange practice to eat more than you need in training, and can feel silly when going out for a 3 hour training run to bring 7 gels, soda, and a bag of chips. However, an iron stomach is truly a secret weapon in an ultra, and nausea can end your day very quickly.

Making friends:

At mile 27 I merged onto a trail at the same time as another runner. A middle-aged Dutch man named Marc from The Hague, we started chatting and I learned he was heading to Rhenen. “Me too!” I exclaimed, “only a bit further!” (68 miles to be exact).

When I told him about the endeavor I was on, he said he was “honored” to share a few kilometers with me. I felt honored he said that.

We ran together for the next 5 miles into Rhenen and exchanged pleasantries about running, American politics, and life in the Netherlands. It was very nice to have some company and just the mental boost I needed. Although there were numerous trails to take into Rhenen, we just so happened to be taking the same exact route into Rhenen.

This interaction is called “trail magic”. Although “support” including a crew or pacer is not allowed during a self-supported FKT, this is allowed because I did not plan for it, and it happened naturally on the trail. Magic.

Thanks for the magic, Marc, and nice meeting you!

WWII History:

A notable part of the UPNL course is that it crosses through several World War II historical sites and fields. Specifically, this is part of the area where Operation Market Garden took place, which was a failed airborne attack by the allies to seize several key bridges in the Netherlands.

Wolfheze fields where the 1st British Airborne Division were dropped. Mile 42

This is a field in Wolfheze where over 2,400 British Paratroopers were dropped during Market Garden, part of the 1st Airborne Division. This was part of the famous “Battle of Arnhem” in 1944, as the allies were making their way from Normandy to Germany. Their objective was to immediately drop in this field and then head to aa bridge in Arnhem, about 10 kilometers away. Over 1,174 from the 1st British Airborne Division were Killed in Action during the battle of Arnhem.

Woeste Hoeve Memorial in Appeldorn. Mile 54

In addition to Market Garden history, I also ran past the Woeste Hoeve Memorial, which commemorates 117 people who were executed on March 18, 1945. These innocent people were killed because a group of Dutch resistance fighters tried to steal a German truck full of meat. After the truck was ambushed, one German survived, and a total of 274 men were executed as a retaliation. 117 were shot in the field I ran past.

As I ran through these fields, I forgot about the scop-swishh-wishh on my back. It didn’t matter anymore, there were more important things going on around me. Silence took over.

I continued to step forward in the fields—now endless acres of farmland—and looked up into the sky. It was perfectly blue. I couldn’t help but to imagine what it looked like 75 years ago, and the brave individuals who fell from the sky in this very spot.

Fields in Woflheze

30 - 70:

Miles 30-70 were full of ups and downs. While my stomach was feeling better, my mind was going in-and-out of the gutter. The heat was setting in, and it’s always a tough pill to swallow that you have such a long way to go with tired legs. This, once again, was a unique part of the solo FKT. In other races, I had crew, family, or other runners to pull me out of a hole. Here, I was alone. I started doing math in my head. While I knew I had a big buffer of time, a few hours can be lost quickly. There’s no room for “breaks” or sitting for 20 minutes. I needed to keep moving, and be in and out of every ‘aid station’ in less than 5 minutes. Fill up the water and go.

I specifically remember mile 52 being challenging. The words “this hurts” rung in my head as my feet dragged along the sand. I was shuffling and I needed to be running. As I widened my stride, the pain spiked for a few seconds, and then subsided. It’s truly incredible how pain can come-and-go so quickly and so often. A few miles later the pain returned—I was in the deep hole again. Then I’d dig out, and run forward…Ups and downs.

At mile 70 I started my caffeine intake with coca-cola and a caffeinated Cliff gel. While this was a nice boost of energy, it caused me to have diarrhea at mile 75, which I could tell was caused by the caffeine — a bit of a shock to the system. This meant an uncomfortable delay of 5-10 minutes, but once it was out of my system I felt much better. (By the way, it’s normal for running race reports to go into this level of detail, if you were wondering).

A hot, sandy path in the Hogue Veluwe. Somewhere around mile 65.

Finally, the sun started to set. There is a unique relationship between an athlete and the sun during a 100+ mile run. It’s your best friend and worst enemy. At the start, you wait patiently for the sun to rise with every step. You wait for light to creep-up between the trees. You look forward to clicking your headlamp off and enjoying the day.

Then, as the day progresses, heat begins to encapsulate every step. While you appreciate the daytime, your mind starts to drift, and look forward to the sun going away. “Just a few degrees cooler would be nice”. This was a repeated thought in my mind. But, sunset is far off. Eight more hours—a full workday. Seven more hours. Six. Three more.

Finally, it arrives. You feel it before you can see it. The breeze sneaks up your shirt and the sweat on your lower back dries-up. It’s pure relief. You made it. Looking up, you see the sun cresting below the trees and “golden hour” begins.

In this moment, the runner has won. The entire day, you’re fighting against heat and getting through the day. Once the sun begins to set, it’s the beginning of the end. It was in this moment I looked up at the sun and said, “I’m still here.”

Golden hour. The sun setting behind me.

Final Stretch

With 30 miles to go, I did the calculation and needed to average 18:30-minute miles to beat the current FKT. This was very doable since I was averaging anywhere from 9:45 - 12:00 per mile.

As a result, the final 30 miles of the race were slower than I’d hoped. The reason for this is quite clear to me: I became complacent, and comfortable with my pace, instead of keeping my foot on the gas.

It was hard to continue to push when I was in a lot of pain, by myself, with no external stimulation. The discomfort of running 70 miles was not new to me, but typically I had other runners, a crew or pacers to encourage me to keep pushing the pace, even late into a race. With this FKT attempt, it was easier to mentally ‘check out’ and shuffle along.

Reviewing the data, there were a few places in the final 30 miles where I did elevate the pace—clocking in an 8:12 mile at 83—but for the most part the final 30 miles were over 11:00 minutes per mile. Next race I will be focusing on finishing hard and finishing fast!

Hallucinations

I’ve run numerous ultras and heard stories from other runners about hallucinations, although never experienced any myself. Until now. I do wrestle with the term “hallucination” as I’ve always considered a hallucination to be something you see on psychedelic drugs, like a leprechaun hopping on a pogo-stick, or a fire-breathing dragon carrying a dominos pizza. In other words, something totally made-up that has no business appearing in that current setting, or a completely fictitious scene. The “hallucinations” I had were more my eyes playing tricks on me, but I guess this is just semantics and terminology preference.

Have you ever been in the woods and thought a stick on the ground was a snake? Or a tree in the woods looked like an animal? These conflicted visuals started at mile 60, and started getting progressively more frequent. By mile 90, I was having these visions every 5 minutes, if not more often. I was genuinely having trouble discerning what was real; there were animals all around me: big-horned buffalos, large black bears waving at me with a slight smile, a school of birds waddling across the trail—a mother duck quacking at me as I ran toward her ducklings—even a reindeer prancing next me. Then, there were visions of police officers standing on the trail in front of me with their arms crossed, slowly bouncing a baton in their hands, waiting for my arrival. I think I was having visions of these police officers because of the concern I had about the forest police putting an end to the journey I worked so hard for. I was getting in my own head. As I got closer to these “visions”, I realized within a meter these were just trees, branches, or rocks.

Looking back, I wonder about my hydration levels and if dehydration played a role. I’d like to rule this out, since I was urinating every 3 hours and my water intake was solid. Calorie intake was also significant, although you can always eat more during an ultra. It was also extremely dusty on the trail, but I was using eye-drops to remedy.

In summary, I’m not sure what caused these visions. The only explanation I can think of is general fatigue combined with the dusk/darkness, which made it harder to see anything, even reality.

Looking great at the finish in Wezep!

Finish

As I made way closer to the finish at Wezep Station, things got silent again. It was nearing 11:30pm, and the world was quiet. Everyone was hibernating, but I was still running. Still a frog, jumping from pad to pad.

scop-swish; scop-swish.

The water in my pack was almost empty, but it didn’t matter. I was almost there.

This was my third 100 mile run, and each finish has felt different. As I mature as a runner, the shear distance of 100 miles no longer intimates me, but instead, it’s the pain. You know it’s going to hurt, but you never know how much and when. Pain depends on where, and how deep, you push. It’s for this reason Ken Chlouber, founder of the Leadville 100, says you have to “make friends with pain, and you’ll never be alone.”

Like a roller coaster, you legitimately don’t know where the twists and turns are, when you’ll go upside-down, when you’ll speed up, and when you’ll slow down. Everything is unknown until it happens. And when it’s over, you smile with joy, appreciation, and adrenaline. You’re sad the ride is over, happy it happened, and relieved the pain is gone. Pure relief. This is what finishing felt like.

I was clinging onto pain, my only friend for nearly 20 hours. When I finished line, I was finally able to let it go. The ride was over.

What’s next?

Food/Electrolyte intake:

15-25oz of water per hour

3 10oz coca-colas

30 chocolate Cliff gels

3 Cliff chewable blocks

1 almond butter and honey sandwich

1 strawberry Pop Tart

3 Gu Waffles

3 bananas

5 Nuun Tablets

15 HAMMER salt + electrolyte tablets

Orange fanta (12oz x 3)

Coca-cola (12oz x 3)

Pocket Pepto Bismol

Gear:

Topo Ultrafly shoes

Ultimate Direction AK Mountain Vest 3.0

Ultimate Direction Body Bottle II Soft Flask - 500ml (x2)

COROS Apex watch (finished with 51% battery)

2L Nathan hydration bladder

Injinji socks

Topo hat

Oakley glasses

Petzl Reactick Headlamp

Body Glide

Vasaline

Eyedrops for dust

Tired legs

Big smile

You don’t need a shiny new pair of shoes to run 100 miles! These are my 10th pair of Topo Ultrafly’s and I’d put over 400 miles on them before starting the UPNL. Okay—now it’s time to retire them.

Thanks for reading! Please leave a comment below if you have any questions.