Boston Marathon - A Different Type of Hurt

At mile 26 of the Boston Marathon, you turn right on Hereford St., then a left on Boylston. You have .2 miles left at the most iconic marathon in the world. Fans are cheering at a deafening volume on both sides of the street. For the last 26 miles you’ve been within arms reach of spectators. But, on this final stretch, barriers keep them at a distance. You’re on your own, stomping the double yellow. You can feel the weight of a thousand eyes, the moment where anyone becomes someone. You’re center-stage and the spotlight is on.

You want to take it all in, so you glance out your periphery, latching onto cheers, allowing them to propel you the final steps. But, nothing is clear, it’s a blur of clapping hands. Your eyes remain fixed straight ahead, gazing at the yellow and blue FINISH.

Many runners cherish these final moments of the Boston Marathon, immortalizing them in memory. Yet, as I reflect, all I can think about is the pain, and how desperately I wanted the race to be over. I’ve run many races in my life, but Boston 2024 hurt different.

I’ve spent the last week thinking more deeply about pain in running: how does it really feel? And why do we keep coming back?

Training

My training for Boston went...pretty great. Since I typically focus on trails and ultras, so this was actually my first training block where I put a legitimate focus on road marathoning. (3rd road marathon ever).

Things kicked off in Thailand in December with heat and humidity training. The miles come easy when you’re exploring new places. When I came back to the U.S., I PR’d my half marathon—twice—first at the Vancouver Lake Half Marathon (1:115:47) and then the Portland Shamrock Half (1:14:40), which I surprisingly won. I was executing 2 workouts per week, consistently, and got myself a pair of Hoka Cielo x1’s. I was running a fairly consistent ~65 miles per week, and I felt ready to race. Things were clicking. I was actually running fast (for me).

Pacing:

One key difference between a marathon and 100 miler is heartrate and pacing. For better or worse, in marathon racing, you are enslaved to the numbers on your watch. Every MP workout , you are fighting and pushing to achieve a pace. For the final 2 months leading up to Boston, I was trying to figure out and dial my marathon pace would be…5:50? 5:55? 6:00? 6:02?

My marathon pace workouts hovered around these times. My COROS race predictor had me pegged at 2:31, which I knew was aggressive and suggested I’d do a fairly even-split after a near-PR on the first half. I was correct in assuming this was unrealistic.

I ended deciding I’d shoot shooting for 5:54 for the first half, which would put me in position to do a sub-2:35:00 if I felt good in the Newton Hills. My A-goal remained doing a sub 2:40.

Looking back, I think this was the right approach, but I should have taken into account the heat. Weather got up to nearly 70F, which slowed me down in the 2nd half. I do believe I was fit enough to run a sub 2:35 on a cooler day and flatter course.

Breaking down the pain:

The pain I felt in Boston wasn’t fatigue, and it wasn’t injury. It was what felt like “peak physiological capability”. Getting everything out of myself that I’m physically capable of for ~2 hours and 40 minutes. From a physiological perspective, this makes sense.

For context, my max heartrate is about 205 beats per minute, and my anarobic threshold is about 200 bpm. A few stats from my race:

Over 80% of the race was at “threshold” in Zone 4 (between 184 - 200 bpm).

My average heartrate was in the high 180’s. For added context, for a 90 minute period in the middle of the race, (15 miles) I had an average heartrate of 191. That’s 93% of my maximum HR!

At one point during every mile my heartrate reached at least 197 bpm.

What this means was that I was near, or at, my aerobic capacity for nearly the whole race. It was my peak physiological fitness on that day. It’s a different type of hurt. You want to stop. You want to walk. You want to do anything other than continue running.

Race days splits

This also gives me a good understanding of my strengths and weaknesses as a marathon runner. I have the ability to endure ~2hrs and 40 minutes of threshold running. This is a good thing, and is typically what elite runners are capable of. That said, if I want to improve my marathon time, I need to “raise my ceiling” and increase my aerobic capacity.

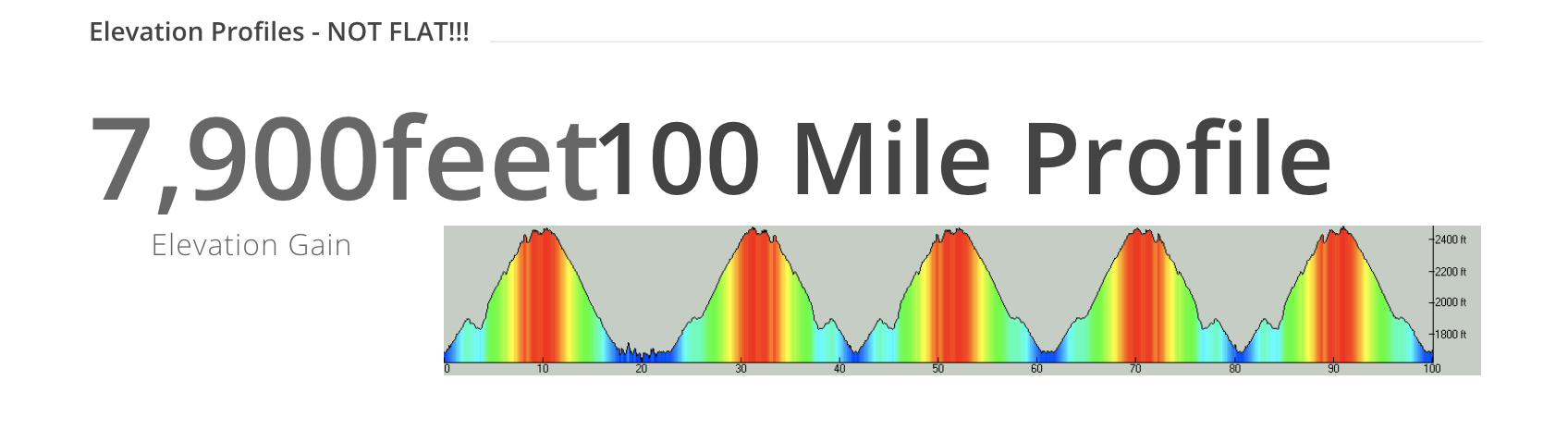

This is incredibly different from a 100 mile race. While yes, I am pushing myself to my limits in a 100 mile race—it’s much more in a mental capacity. Most of 100 milers are run in Zone 2; for the first 70 miles your pace could be equivalent to a Sunday morning social run with friends, and true racing doesn’t begin until the late stages.

Giving a few high-fives to my nieces and nephews at mile 14

People often ask me the difference between a marathon mile race and 100 mile races. I realized is that marathoning is about reaching your peak physiological capabilities: it’s more of a scientific equation to hit certain paces within certain heart-rate/effort thresholds. 100 mile races are a question of troubleshooting and resourcefulness. They’re very different.

What I’ve come to realize s that I simply love the variety of feelings that each distance and surface offers. A trail 100 miler feels and hurts differently than a mile repeats on a track.

Runners love to suffer — suffering means improvement. And while pain comes along with suffering, I’m a better runner knowing how and why we feel different types of pain. I’m ready to keep improving.

Boston Marathon 2024

2:39:23

412 / 26,491